The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (THECB) requires that courses in each Core Curriculum component area are embedded with the Core Objectives assigned to that component area. UT Austin faculty developed the Student Competencies which are used to define each Core Curriculum component area and have embedded the required Core Objectives within the Student Competencies.

THECB definitions for each Core Objective are:

Critical Thinking Skills (CT): to include creative thinking, innovation, inquiry, and analysis, evaluation and synthesis of information.

Critical Thinking Skills (CT): to include creative thinking, innovation, inquiry, and analysis, evaluation and synthesis of information.

Communication Skills (COMM): to include effective development, interpretation and expression of ideas through written, oral and visual communication.

Communication Skills (COMM): to include effective development, interpretation and expression of ideas through written, oral and visual communication.

Empirical and Quantitative Skills (EQS): to include the manipulation and analysis of numerical data or observable facts resulting in informed conclusions.

Empirical and Quantitative Skills (EQS): to include the manipulation and analysis of numerical data or observable facts resulting in informed conclusions.

Teamwork (TW): to include the ability to consider different points of view and to work effectively with others to support a shared purpose or goal.

Teamwork (TW): to include the ability to consider different points of view and to work effectively with others to support a shared purpose or goal.

Social Responsibility (SR): to include intercultural competence, knowledge of civic responsibility, and the ability to engage effectively in regional, national, and global communities.

Social Responsibility (SR): to include intercultural competence, knowledge of civic responsibility, and the ability to engage effectively in regional, national, and global communities.

Personal Responsibility (PR): to include the ability to connect choices, actions and consequences to ethical decision-making.

Personal Responsibility (PR): to include the ability to connect choices, actions and consequences to ethical decision-making.

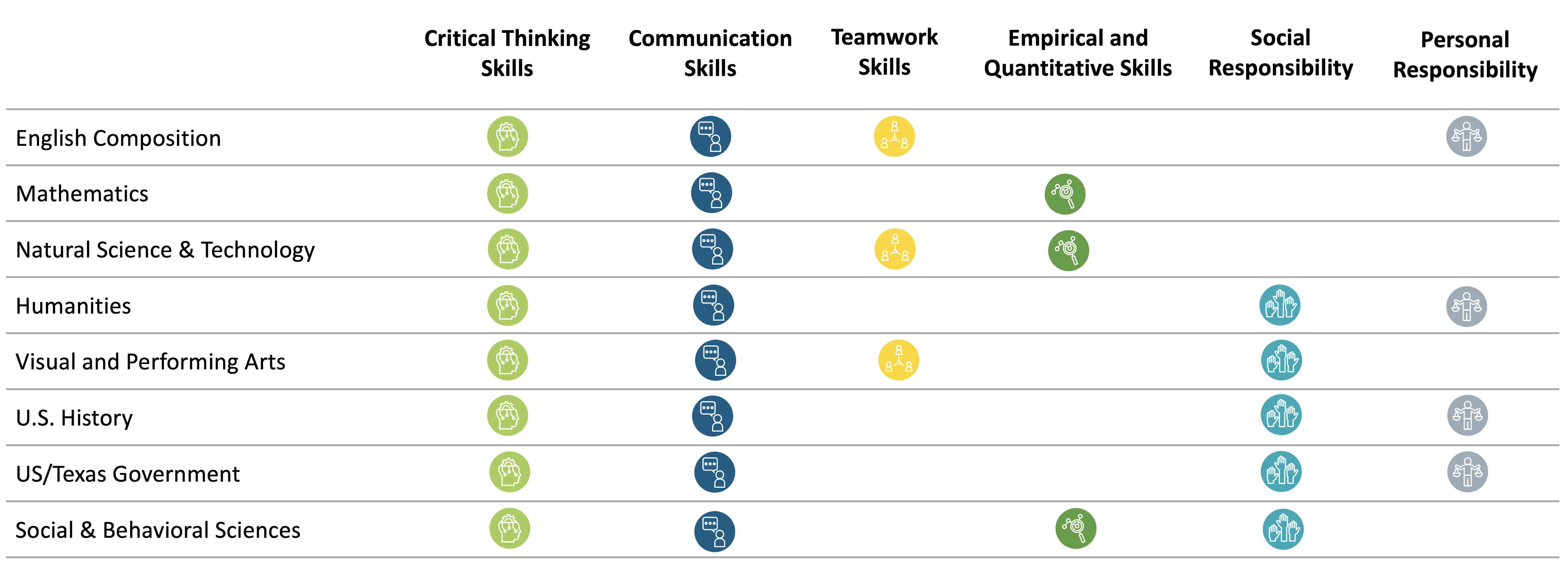

The table below shows the Core Objectives required in each Core Curriculum component area:

Included below are sample responses from approved Core Course proposals showing how the course provides students exposure to the required Core Objectives.

Critical Thinking Skills (CT) responses

Sample response from a natural science and technology course:

Homework exercises include exploration of alternative data sets relevant to particular hazard scenarios; homework and in-class discussions will center on real-world problems and the application of scientific methods to address those problems. Examples include fault lubrication and induced seismicity, the potential for groundwater contamination by hydraulic fracturing, forecasting consequences of impending hazards (e.g., hurricanes), mechanisms for mitigating serious consequences of hazards, and the utilization of data from recent hazard events to improve scientific understanding of hazards and improve prediction of future outcomes.

Sample response from a mathematics course:

Through multiple problem-set assignments, lab sessions, and in-class demonstrations, students learn about and must communicate how to solve practical problems in social statistics. A sample in-class problem the class works on involves, for example, testing the hypothesis that preschoolers watch in excess of 20 hours of TV a week; students are asked to consider data from a sample of preschoolers, to calculate the correct point estimate, and test whether the result is significantly greater than 20. Homework problem sets contain many more demonstrations of how to correctly apply a statistical concept to data.

Sample response from a visual and performing arts course:

The syllabus includes the list of required performances, which are meant to span the breadth of performing art forms, as well as a specific unit around engaging more directly with visual art forms. The Critical Response Process listed above will help students analyze, evaluate, and respond to works of art in an organized and constructive manner that requires a deeper engagement and analysis.

Communication Skills (COMM) responses

Sample response from a mathematics course:

Students communicate results via problem sets and tests, both of which focus on applying concepts correctly to a research situation, which facilitates development of the correct understanding and communication of mathematical concepts.

Sample response from a visual and performing arts course:

Course activities include regular opportunities to develop writing communication skills, both in an immediate response to a live performance and as a longer-term critical response to previously written work (see syllabus for description of book report activity). The course final project directly challenges students to develop communication skills necessary to engage others in appreciation of and participation in the arts.

Sample response from a mathematics course:

Students will be required to analyze, display (visually) and write-up the results of their data analysis using appropriate statistical reporting style guidelines from the American Psychological Association, including statistical abbreviations and symbols that are common in social psychological research.

Empirical and Quantitative Skills (EQS) responses

Sample response from a natural science and technology course:

Exercises will involve the application of physics, mathematics, chemistry, and biology to evaluate events on the Earth’s surface connected to natural hazards. Specific applications of quantitative methods will be exemplified via probability and statistics used in predicting hazards, quantitative and computer models used to predict hazard impacts (e.g., travel time of tsunamis from source to populated coastal areas, rapidity of floodwater movement, storm surge prediction, etc.

Sample response from a social and behavioral science course:

Students are exposed to statistical data in the course to learn about various topics – e.g., ethnic food preferences in the U.S., poverty and racial trends in cities. Questions on the exams, quizzes and in-class and take-home assignments assess understanding. They work in small groups of two to three to find real-world examples related to this data and share with the class. Students are exposed to videos and examples of experimental research related to consumer choice, to motivational research related to consumer decision-making and survey research related to values and attitudes. Students take surveys and see the results in real-time. Take-home assignments and in-class discussions provide opportunities to voice and write about the research.

Sample response from a mathematics course:

Students learn basic, core competence in statistics, specifically: measures of central tendency, measures of dispersion, frequency distributions, how to analyze bivariate problems (including through correlation, linear regression, and chi-square approaches), elements of probabilistic reasoning (including mutual exclusivity, independent and non-independent events, conditional probability, and rules of probability), the concept of random variables, binomial distributions, normal distributions, p-values, and inferential statistics for one- and two-population cases.

Teamwork (TW) responses

Sample response from a visual and performing arts course:

Daily class exercises, as well as discussion sections, systematically involve in-class discussion of varying perspectives; multiple in-class exercises throughout the semester involve group work of various sorts (group transcriptions and discussions of musical examples, collective performance/improvisation and discussion of the practices undertaken, etc).

Sample response from a natural science and technology course:

Students work in teams during most unit activities to discuss their initial understanding of the material, share their common knowledge, learn from each other and then advance their knowledge together. Team activities include think-pair-share, team games (e.g., each student is a reservoir of Carbon, they roll die and determine where their C atom goes and share out to their team), learning jigsaws, and oral presentations (during lab). Teams may be self or instructor organized depending on the activity. For example, an activity in Module 1 helps students develop their understanding of geoscience thinking and methodology by analyzing patterns on a cube with 5 visible sides. Each team uses their observations to hypothesize what is on the bottom of the cube. Students first work in groups of 3-4 making observations and developing a hypothesis. They then share 1 observation per group to the class. We discuss whether increased collaboration among groups helped students refine their hypothesis. We also discuss how multiple lines of evidence can be used to develop hypotheses. Students then flip the cube over and discover that they can see only part of the pattern on the bottom of the cube. They develop a “result” within each group and then share the result with the class – to discover that each group has different results and only by combining results can they come to the correct conclusion.

Social Responsibility (SR) responses

Sample response from a visual and performing arts course:

Many of the course objectives listed on the syllabus promote social responsibility through active participation as an audience member in the arts. Moreover, this course will prepare students to actively participate in and support their local arts presenting organizations, showing the importance of these organizations to civic life. The students will engage with multicultural works of art and/or artists with both western and non-western roots, including inquiry into each work’s cultural context and meaning. This course will also directly engage the topics of “Artistic Citizenship” and “Artivism,” exploring ways in which art can be harnessed to fulfill civic responsibility and engagement through informing the public of social issues, providing critical stances on culture and politics, utilizing sustainable materials, and engaging underserved populations in artistic endeavors.

Sample response from a social and behavioral science course:

Students will take two quizzes that test knowledge of African-American history and knowledge of the history of Black Studies with the context of Blacks at UT Austin.

Sample response from a humanities course:

Throughout the course, and in the essays assigned, students reflect upon the historical and social implications of a wide variety of texts and consequentially upon their own interpretations of how these cultural documents matter. That is, students are asked to consider ethical questions of cultural expression within their historical contexts, while also considering their implications within a contemporary framework, both personal and societal.

Sample response from a US history course:

My lectures and the assigned readings emphasize that the importance of studying history is not simply to learn “what happened.” We begin with “what happened,” but students are challenged to consider the sources of accounts of “what happened,” and, then, to ask why something happened. For example, lectures and readings ask students to understand why, before 1763 most Americans were proud to be part of the British Empire and why, just one decade later, many colonists were demonstrating against British “reforms.” This, and other questions, cannot be answered without looking at contemporary events and the multifaceted context of those events.

I pose these questions in class, and students must address similar questions in their essay exams.

Personal Responsibility (PR) responses

Sample response from a US history course:

By close reading of primary historical documents – letters, diaries, speeches, government documents, newspaper accounts – students will reconstruct the presidential decision process. They will make the arguments for and against presidential decisions. They will explain and defend the decisions they would have made in the president’s place. Case study materials will include Abraham Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation, the dropping of the atomic bomb, Richard Nixon and the Pentagon Papers, use of torture (“enhanced interrogation”), and other topics.

Sample response from a humanities course:

The best literature expresses, engages with, and occasionally critiques the values of its characters and the societies in which they live. (In this way, literature functions as both a mirror and a lamp: it reflects as much as it illuminates.) In reading, discussing, and writing about a piece of literature, E316K students are required to consider the circumstances in which it was produced. They also grapple with the question of what “value” means to different people in different social and historical contexts.

For instance, when studying The Merchant of Venice, students have to make key and at times uncomfortable interpretative decisions about Shakespeare’s representation of Shylock, the seemingly cruel Jewish moneylender who refuses to forgive Antonio’s debt. What is Shakespeare saying here about the values of his characters and their society? Similarly, E316K students must confront the paradox at the heart of the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself: Douglass cherishes the values of freedom, courage, and empathy, yet the society in which he lived valued him only for his economic worth. What happens when values and perspectives clash so violently? Finally, with Kate Chopin’s The Awakening students debate the primary question with which the novel’s protagonist struggles: is Edna’s primary responsibility to herself or to her children? How are we to understand her final swim into oblivion—as an abdication of her most important responsibilities or as an act of personal liberty?

Sample response from a humanities course:

Throughout the course, and in the essays assigned, students reflect upon the historical and social implications of a wide variety of texts and consequentially upon their own interpretations of how these cultural documents matter. That is, students are asked to consider ethical questions of cultural expression within their historical contexts, while also considering their implications within a contemporary framework, both personal and societal.

Sample response from a US history course:

My lectures and the assigned readings emphasize that the importance of studying history is not simply to learn “what happened.” We begin with “what happened,” but students are challenged to consider the sources of accounts of “what happened,” and, then, to ask why something happened. For example, lectures and readings ask students to understand why, before1763 most Americans were proud to be part of the British Empire and why, just one decade later, many colonists were demonstrating against British “reforms.” This, and other questions, cannot be answered without looking at contemporary events and the multifaceted context f those events.

I pose these questions in class, and students must address similar questions in their essay exams.

Sample response from a US/TX government course:

The course is centrally concerned with issues of justice, ethics, civic duty, and personal and social responsibility. Students debate moral and philosophical questions having to do with freedom, slavery, religion, equality, citizenship, political participation, and civic responsibility. The students read and discuss classic works on these topics as well as the speeches of important U.S. political figures.